The Director of Education at the Schomberg Research Center for Black Culture, Brian Jones, was very kind to tour us through parts of the building and to introduce us to two of the curators of their departments at the Center. He also informed us about the important people that made the Center what it is today and a bit of its history – It was interesting to learn about Arturo Alfonso Schomburg and that his collection was bought for $10,000 in 1926 by the New York Public Library.

Before we started our tour, we were asked to try and guess the number of items and artifacts in the collection and to state the programs that we are all in, for context, before walking us through the Latimer/Edison Gallery. The Center’s exhibit space is small but large enough to walk a group through to talk about the materials represented. The exhibit currently on view is Crusader: Martin Luther King Jr. and showcased photographs of King and his wife traveling overseas to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, in addition to text to accompany the images. Along with formal photographs printed in a dark room and a large vinyl image, there were Polaroids of the family that have a more snapshot and candid feel to them.

From the exhibit space, we were brought down to the conference room on the lower level to meet with Cheryl Beredo, Curator of the Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division. She explained the best practice for utilizing the Schomberg for research is to make a 10-minute appointment to talk to an employee about their interest. From there, advice can be given on where to go to do research. It was also mentioned that maybe a 5-minute browse through the collections before meeting with an employee may help, as well. After the class found out collections are divided up between divisions, the question of the original location of materials came up. Regarding, dividing up the collections to separate divisions, Cheryl responded that they’ll have access points leading the items back to their original collection. One of the most important statements that Cheryl made sure we understood was if we use a source from the Center to make sure to cite correctly. She said far too many times sources are not cited correctly.

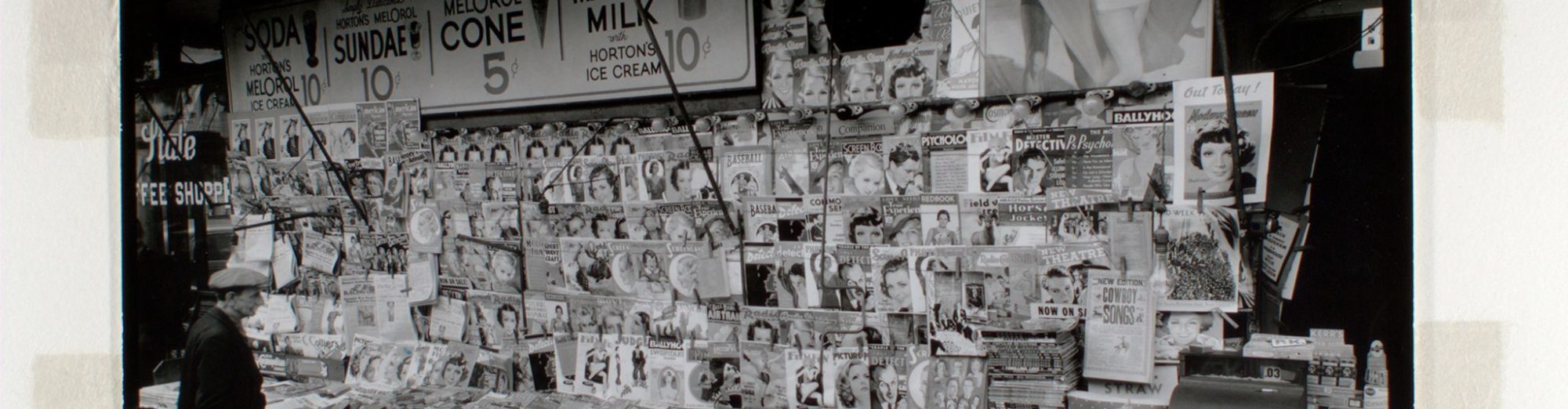

Michael Mery was the next employee we met with and he is the acting Curator of the Photographs and Prints Division. He brought with him his white gloves and an archival box stock full of historic photographs in mylar sleeves – just a sampling of the 500,000 plus photographs and prints in his possession. Before he presented some of the photographs he brought with him, he allowed all of us to ask questions. Regarding some of the classifications of photographs he has, he stated there are photos on the Harlem Renaissance, religion, jazz, military, and prominent and not so prominent photographers. The photographs he pulled out were of WWI African American soldiers in France. I was very impressed with the way the photographer superimposed imagery into the photographs, like a picture of a significant other and a musical instrument. Something I was excited to hear about was some of the more prominent photographers in the collection. Eli Reed, who is a photographer with the Magnum Agency, is someone who’s artwork I’ve worked with and enjoyed viewing while in Georgia. Another photographer I was excited to hear about in the collection was Gordon Parks. I have also worked closely with Parks’ artwork and researched his Segregation Story to create a tour map of locations where he photographed the Thornton family for my Documentary Photography and Film course. On our way out we walked by the original theatre and took time to look over the Cosmogram in the center of the lobby. I look forward to utilizing the Center for research in the near future.