The Eclipse Archive is a collection of digital facsimiles of radical small-press poetry written primarily between 1975 and 2000. Its name a nod to Sun & Moon Press, an important publisher of experimental work during the period, Eclipse was founded around 2002 by poet and scholar Craig Dworkin, professor of English at the University of Utah. Dworkin co-manages the archive with Danny Snelson, associate professor of English at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Both Dworkin’s and Snelson’s scholarly research involves the materiality of contemporary poetry: Dworkin’s monographs Reading the Illegible (2003) and No Medium (2013) feature erased, defaced, blank, and otherwise unreadable texts, while Snelson’s work tracks media formats in poetry databases. This engagement with, and concern for, the primary source materials (both print and born-digital) of 20th-century experimental poetry informs Eclipse’s underlying ethos, and connects the archive to related avant-garde collections in UbuWeb and PennSound.

In interviews, Dworkin routinely links his motivation for establishing Eclipse to the need to make accessible the many limited-edition, avant-garde books and periodicals that were going out of print. “As someone committed to teaching such work, and to having a rigorous scholarly treatment of such work,” Dworkin told Entropy in 2017, “I realized that its availability to students and researchers was imperative.” This echoes an interview with Jacket2 in 2016, in which Dworkin says: “There were scholarly articles starting to come out about the history of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry, 70s and 80s avant-garde in America—and people were writing about it without having ever read the primary documents. In any other field in literary history [this] would be unthinkable; you’d never write a book about Renaissance poetry and say, ‘Well, yeah, I’ve never actually read John Donne, but let me tell you what I think about him.’”

Despite its commitment to discipline-wide recovery, the Eclipse Archive is fundamentally a home-grown effort. Dworkin taught himself to cobble together the archive’s original HTML by working through an introduction to web design book he checked out from the library. And, of the facsimiles currently up on the archive, most have come directly from Dworkin’s personal collection, which he says he scans on a ten-year-old Canon printer late at night after his son goes to bed. This intimate connection to the archive sometimes comes at a price, with Dworkin occasionally electing to destroy binding in order to make his copies of print texts more readily available to others online.

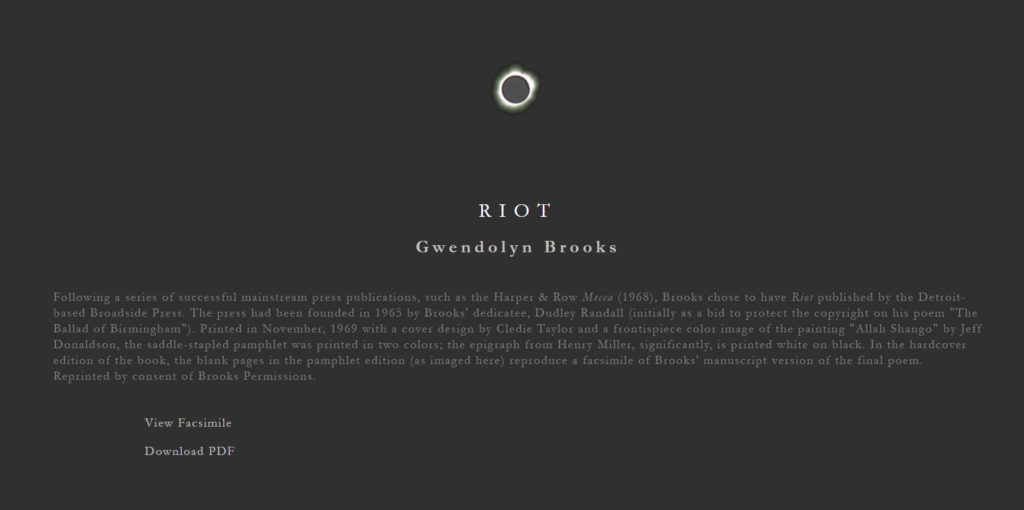

Eclipse Archive entry for Gwendolyn Brooks’s RIOT, including bibliographic information

Whether their work requires destructive methods or not, though, Dworkin and Snelson are nothing if not thorough. They insist on securing permissions from authors and presses before admitting a text into the archive, something they acknowledge their peer archives sometimes do not do. They commit to scanning each page—including (or, for Dworkin, especially) the blank ones—in full color at a high-resolution 600 dpi, even when it means effectively doubling the file size and hosting costs. There is also at least some effort to capture significant bibliographic metadata from the text, with facsimiles typically accompanied by notes on anything from the text’s circulation history to its illustration credits to the typography or type of binding methods used.

This metadata, however, is not captured consistently or made available in any structured form, which seems to be an intentional choice, as Dworkin says in the Jacket2 interview: “Part of the ideology behind Eclipse is that I don’t want to try and predict or imagine or limit what people will do with the materials. I want to make as much available as possible. This is why there’s no metadata; I’m not tagging.”

Future projects, either by Dworkin and Snelson or by their peers, might want to consider how actively collecting and sharing metadata about the materiality of these texts would help develop Eclipse into a more intentional educational resource. Such contributions would likely have an outsize benefit to those studying the texts collected under Eclipse’s “Black Radical Tradition” category, an important counter to the perceived whiteness of the avant-garde archives. Because the rise in the study of Black literature in the last quarter-to-half century has coincided with the relative decline in the practice of scholarly bibliography—the study of books as physical objects—one consequence of this divergence has been that the field relies on bibliographical reference tools that tend to define works worth studying as only those produced in feature-length forms (usually novels) from elite publishing houses. This limitation arguably reinforces a color barrier for literary scholars studying the complex publishing histories of radical small-press work—including pamphlets, chapbooks, periodicals, and low-cost reprintings—that reached wide audiences in the Black community. Since Eclipse, in some instances, may provide the only known digitized version of the Black Radical texts, doubling down on their efforts to contribute not only primary source materials but also significant metadata about these materials would go a long way toward recovering these minor texts into the larger canon of the American avant-garde.